Gerunds: a simple solution to architecture exhaustion

The following is the more engaging parts from a talk I gave at Seattle.rb promoting a lightweight, PORO, but potentially controversial alternative to popular heavy-weight architectural solutions like DCI, Clean Architecture, and Trailblazer.

If you do backend or full stack software engineering with OOP frameworks like Rails, Django, and similar, I have something I’d like you to try. It’s a simple, natural way to express behavior that’s either bloating models, or is spread around various architectural components like service objects, form models, presenters, and similar.

To be sure, count yourself lucky if you have good structure in your app; even if it’s a bit complex, it’s vastly superior to fat controllers or fat models for keeping velocity up.

You have to admit though - wasn’t it nice when your app was smaller, and your domain models were just translations of things you’d see in use cases? Sure, User had a few long methods, but you didn’t have UserPresenter, UserRegistrationService, and whatever else, all with their own interfaces and implementations to manage, none inspired by delivering customer value.

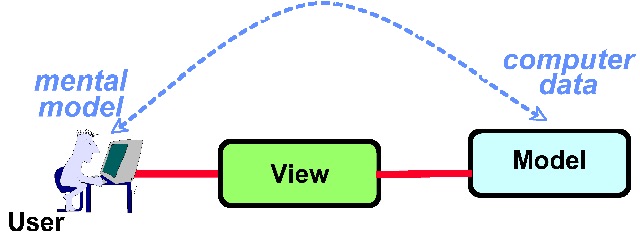

I mean, transparent domain modeling was the original promise of Model-View-Controller (MVC). You’re supposed to spend most of your energy translating users’ mental models to code - the M - and let views and controllers expose it to the world:

Well, the authors of Model-View-Controller realized OOP was missing something:

While objects capture structure well, they fail to capture system action.

The DCI Architecture: A New Vision of Object-Oriented Programming, 2009

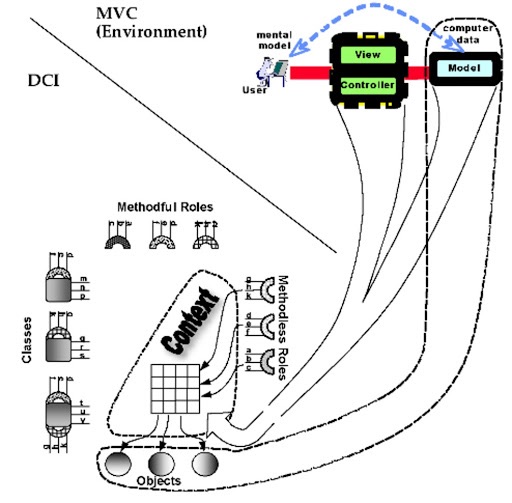

So, they proposed a fix that looks like this:

I actually think DCI is really smart, but… yikes. DCI could probably handle any level of complexity, which is a good tool to have in your pocket. If you just want to put a bit of registration logic somewhere other than User, though, it’s not worth pulling in all that extra jargon. I don’t need a Context to manage a Role to extend the User so it can participate in a registration Interaction - there’s just got to be a more natural way.

This post is about a simple technique I’ve been experimenting with for a couple years that can serve as the step prior to adopting DCI, Clean Architecture, Trailblazer, or the like. This technique might scale just as well or better, actually, but I haven’t tried it for that long so I won’t presume.

The good news

The good news is you can try it today after nothing more than being convinced. It requires no dependencies or gems, and extremely little buy in. You can do it in a new or existing project within any other structure or framework needing a place for business logic.

As if that wasn’t enough, if you ever outgrow it, it will map well to any of the architectures I’ll mention. They all have in common a core focus on keeping data “barely smart” while giving first-class support to business logic. You’ll have those two pillars, and can map them to your architecture of choice later.

Finally, the technique should apply to many if not all OOP languages. Even though all the examples are for Ruby on Rails, and this post assumes familiarity with both Ruby and Rails, “where do I put my business logic” is a fairly common OOP issue (see ex. this Django post on service objects).

The “bad” news

There’s “bad” news though, and it’s why this post is so long.

I’m going to try to talk you into a new naming convention, and I know how contentious naming conventions are. This naming convention has taken time to grow on me, too, but I still think it makes sense.

I’m also going to try to convince you, just sometimes… to prefer inheritance over composition. 😦

As if that wasn’t enough, and only if you’re with me on the other two, I’m also going to advocate for a return to ActiveRecord callbacks. 😦😦

I know. I know. But I think it’ll be worth it.

Overview

- Why gerunds are ****ing great argues for the naming convention.

- Hating on decorators isn’t something you see every day!

- Here’s the crazy part where I advocate for inheritance over composition.

- A joyful return to ActiveRecord callbacks just in case you weren’t quite ready to throw your hands up.

- My own experiences growing Rails with gerunds.

- Trailblazer vs gerunds is a very representative example (with code).

- Summary & Further Reading

Why gerunds are ****ing great

How do we express actions in natural language? With gerunds, aka -ing words:

Gerund: a verb that acts as a noun, ending in -ing, becoming the subject or object of a sentence

subject enjoys

verb drinking

object Your order

subject is

verb processing

object When the user

subject is

verb registering

object

So when we talk about a subject performing actions, the verb becomes the object.

Hey, wait, we do “object-oriented” programming right? Why haven’t I used a gerund in code then?

Well, I think we can use this fact of grammar to consider changing the way we name system actions, thereby improving the expressiveness of our domain models.

Gotta put the code somewhere

In my experience, this is how a lot of behavior starts out: instance methods on core domain models 🤢

Order#process

User#register

Product#decrement_qty

Eventually, someone makes service objects (yay!):

Order::Processor#process

User::Registrar#register

Product::Updater#decrement_qty

Why does every object have to be a noun though? Since -ing words are literally the object of the sentences we use to describe actions, what about:

Order::Processing#save

User::Registering#save

Product::Updating#save

I used #save here because that’s what ActiveRecord callbacks use, more on that in a bit

Make Ruby natural, not simple, in a way that mirrors life.

— Yukihiro Matsumoto

Well, I have been finding the gerund style to be a much more natural way to model action than the usual service object nomenclature. It reads well (the class name plus method signature makes a valid sentence), calls out the transient nature of the operation, and naturally inspires a consistent interface.

You don’t have to take my word for it yet. Reserve judgment until the end, where we have real world code examples.

Question from the audience: what’s wrong with service objects?

Service objects are a top-notch strategy, to be sure. Extracting behavior from a core model to a service object decreases bloat on the core model, which is important for keeping velocity up.

They do come with trade-offs though:

- Feature envy: The service object by definition will exhibit strong feature envy, especially if it’s just for a single model.

- Naming: The -er suffix is passable, but I’ve always wanted something different. Over time, there’s just… so… many… nouns…

- Complexity: Generally increases due to adding another layer of objects that all need names, interfaces, implementation choices, etc.

To jump to a real-world example of service object bloat, see the Trailblazer vs gerund section.

Next up, some cathartic decorator bashing.

Hating on decorators

The decorator pattern is an extremely common way to extend core models in Rails. Sometimes for service objects, but especially for view models, presenters, form models, etc.

This is what the Gang of Four have to say about decorators:

[The decorator pattern is used to] Attach additional responsibilities to an object dynamically. Decorators provide a flexible alternative to subclassing for extending functionality.

— Design Patterns (1994), emphasis mine

Well, I’ve tried many times to like them. I forget what all I’ve tried at this point, but it includes popular delegation-based gems like Draper and cells, a refinement-based presenter gem, even just rolling my own presenters via SimpleDelegator.

As a real-world example, InPlay (my startup) extends Schedule domain models with some display helpers. Sometimes we want to index the output of the helpers into Elasticsearch or consume them in the React-based part of our website, both depending on to_json. This is in addition to normal server-side-rendered pages in the rest of the site that use the schedules in plain Ruby.

Surprisingly, all of the above-mentioned decorator strategies would fail to work for my use case.

Here’s a simplified example to expose the issue:

TodoItem extended with a decorator

require 'active_support/all'

class TodoItem < Struct.new(:name, :id, keyword_init: true)

end

class TodoItemPresenter < SimpleDelegator

def name

super.titleize

end

def as_json

super.merge(path: "/todo_items/#{id}")

end

end

Implementation note: ActiveSupport provides Object#to_json, returning a JSON string, which JSON-ifies the hash returned by Object#as_json, aslo provided by ActiveSupport

Let’s see what happens when we try to use, in the Gang’s words, this “flexible alternative to subclassing:”

# Instantiating a TodoItem and its presenter:

item = TodoItem.new(name: 'foo', id: 1)

presenter = TodoItemPresenter.new(item)

# Calling a simple accessor on the presenter:

presenter.name

#=> "Foo"

# Yep, titlized. Now let's try getting some JSON:

presenter.as_json

#=> {name: "foo", id: 1, path: "/todo_items/1"}

# OOPS!!! Name is NOT titleized. 😯

#

# What about #to_json?

presenter.to_json

#=> %s({"name": "foo", "id": 1})

# EVEN WORSE! No titleization, no path. 😩

Why doesn’t this work as you initially expect?

TodoItemPresenter#as_json:

- calls

super, which forwards toTodoItem TodoItem#as_jsonusesTodoItem#name, notTodoItemPresenter#name.TodoItemPresenter#as_jsonthen mergespathinto the output ofTodoItem#as_json, so there’s that.

TodoItemPresenter#to_json:

- is not defined, so forwards to

TodoItem TodoItem#to_jsoncallsTodoItem#as_jsonnotTodoItemPresenter#as_json.- There is no 3. It never touches

TodoItemPresenter#as_jsonso we get none of our extended functionality.

I was happy to notice this issue mentioned in Wikipedia’s drawbacks section of the composition over inheritance entry:

One common drawback of using composition instead of inheritance is that methods being provided by individual components may have to be implemented in the derived type.

This issue is also referred to more broadly as self-schizophrenia, although it’s important to point out the innacuracy of this term. It means to describe a mental break involving multiple identities, but if we must make mental health analogies, this would be dissociative identity disorder. Among all the things a person with schizophrenia will suffer, changing among multiple personalities is not one of them. 🤷♂️

Anyways, considering all this, are decorators really a “flexible alternative to subclassing?” They’re an alternative, and flexible due to having no predefined relationship with the decorated object, but also have some potentially surprising behavior exactly because of that lack of relationship. They really aren’t a great choice for extending domain models.

Even though we haven’t gone in depth about re-embracing inheritance yet (we will next), since the presenter is fresh in your mind, let’s go ahead and compare the presenter with an inheritance-based implementation.

TodoItem extended with inheritance

Let’s look at the same example as above, but using inheritance and gerunds instead of decorators:

require 'active_support/all'

class TodoItem < Struct.new(:name, :id, keyword_init: true)

end

class TodoItem::Displaying < TodoItem

def name

super.titleize

end

def as_json

super.merge(path: "/todo_items/#{id}")

end

end

We don’t need to break this down, it all just works, because of course it does:

item = TodoItem::Displaying.new(name: 'foo', id: 1)

item.name

#=> "Foo"

item.as_json

#=> {name: "Foo", id: 1, path: "/todo_items/1"}

item.to_json

#=> %s({"name": "Foo", "id": 1, "path": "/todo_items/1"})

We get everything we want, and remove a layer of jargon while we’re at it.

🎉

Yes, really, inheritance over composition sometimes

There is deeply ingrained cultural wisdom among Senior developers to prefer composition over inheritance (Design Patterns (1994)), and with decent reason. See the wikipedia page on composition over inheritance for an overview, but TL;DR using inheritance for modeling complex combinations of behavior can quickly get obtuse, or might even be impossible, depending on your use case.

Let’s break it down. Why are we to prefer composition over inheritance?

Caveat: I’m sure the following is non-exhaustive, but these are my top inheritance issues

Inheritance is bad at dynamic behavior

[Using composition over inheritance], alternative implementation of system behaviors is accomplished by providing another class that implements the desired behavior interface. A class that contains a reference to an interface can support implementations of the interface - a choice that can be delayed until run time.

— Wikipedia, emphasis mine

Wikipedia’s example, from Head First Design Patterns (2004), demonstrates how one could implement various kinds of duck calls and flight methods to be specified at runtime.

For example, you could instantiate a duck, who at first might use CannotFly as it’s flying behavior, to be upgraded to FlyWithWings, and if it’s lucky, FlyRocketPowered. Perhaps its rockets break, so it’s downgraded to the FlyWithWings behavior. Critically, you could do this all on the same long-lived Duck instance, and with this strategy pattern you could change the behavior all day long without issue.

Due to the short-lived nature of domain models in Rails’ request/response cycle, in 12 years of coding Rails apps, I’ve needed to do something like this on a domain model exactly zero times.

🤔

Inheritance is bad at sharing code

I recently ran across this article, Goodbye Object-Oriented Programming, which does a good job of highlighting the downsides of inheritance (and more). TL;DR complex inheritance hierarchies for sharing code makes for bad times. Go read it if you need convincing, it’ll save me some keystrokes.

Unlike that article though, my conclusion isn’t to throw away OOP entirely.

I agree with Reenskaug and Coplien when they said objects capture structure well. So, instead of quitting the whole OOP thing and coding our websites in - what then, Haskell? - let’s use OOP’s strengths for our domain modeling and appropriate alternatives for sharing code.

Inheritance is GREAT at single-purpose extension

So inheritance is bad at dynamic behavior and sharing code, probably other things too. OK, but I don’t need highly dynamic behavior in my domain models, and I have lots of other ways to reuse code between objects.

What I do need, every day, is a natural way to translate use cases into code without complicating, breaking, or majorly refactoring whatever I did yesterday.

Not just to make it work initially, but to communicate my intent clearly to my future self and others long after the use case is top of mind.

For example, this could be logic for registering a User, whether as part of a registration wall, a sub-feature that needs to include a registration step, an admin area that can create registered users, or an API. The core User definitely doesn’t need to know how registration works, but why not User::Registering?

Or this could be helpers for displaying a Schedule, maybe in an email, web page, or a JSON API. Schedule doesn’t need to always carry display-specific bloat around, but when you need it, it feels natural for the schedule to temporarily dress for the role via Schedule::Viewing.

I’m proposing object extensions that are behavior-specific and throw-away by design. They clearly communicate no intent to be pillars of extensibility or reuse, and cannot be hot-swapped mid stream. For that non compromise, we get to reclaim the intuitive expressiveness of inheritance for coding our use cases.

Question from the audience: can gerunds share behavior?

I use one of two ways to share code in gerunds, both of which keep the naming convention but might change the implementation.

One, keep the use-case-specific gerunds and share code any old way - module-based multiple inheritance, delegation to a service object, whatever.

For example, if you had Payment::CreditCard::Proccessing and Payment::Bitcoin::Processing that already inherited from their respective payment subtypes, a Payment::BaseProcessing module could share validations while *::Processing implement different authorize and capture strategies.

Two, you could implement the behavior in a module meant to be applied at runtime.

For example, you could extend a Payment instance with a Payment::Processing module before the payment is saved. Inspired by DCI, I had good results putting action-specific behavior in runtime extensions before reading Growing Rails Applications in Practice, where they advocate for simple inheritance. I haven’t had a need to runtime extension recently, but I consider it definitely on the table.

Performance note: prior to Ruby 2.1 there was a performance penalty for runtime extension, but I’ve personally measured that it is now a non-issue.

Sidebar time!

A joyful return to ActiveRecord callbacks

Important sidebar before our deep dive into examples: gerunds also let you reclaim ActiveRecord callbacks!

Callbacks on core models have fallen out of fashion, and for very good reason. They will inevitably become a central source of complexity as a project grows, since sometimes you’ll want them, sometimes you won’t.

When (not if) someone messes up the conditionals managing your callbacks, and when (not if) someone accidentally triggers one that’s not supposed to run in ex. a data backfill, it can be a real bummer. Every Rails project I’ve worked on, even while contracting, has accidentally sent an email blast to users due to a data migration or backfill accident with callbacks! 😮

So trust me, I know the dangers of callbacks. However, if your callbacks are contained inside behavior-specific gerunds, there is no risk of conflict with other use cases or accidental triggering.

In your gerunds, the callback API becomes an asset again:

- You have a well-understood, feature-full, declarative API to describe the steps required to fulfill a use case via the

ActiveModel::CallbacksAPI. - You have well-understood semantics around stopping the use case from executing via

throw :abort, then providing feedback to the user, all via theActiveModel::ErrorsAPI. - Your gerunds all have a consistent one-method interface,

#save, which is also the same as your base domain models.

My own experiences growing Rails with gerunds

OK, finally, enough talk. Let’s get into some real code examples.

A good many years ago, my User class used to be a registration wall, something along the lines of:

class User < ApplicationRecord

with_options on: :create do

validates :password,

confirmation: true,

presence: true

validates :password_confirmation,

presence: true,

if: :password_changed?

end

# not a great idea - just for example's sake

after_create :send_welcome_mail

# [...]

end

Drawbacks:

- Cannot create a user without sending a welcome email

- Validation & callbacks conditional on specifically the ActiveRecord#create callback

- Someone will eventually need different behavior and add a flag

- Flags lead to bugs, complex state machines, or both

As the project grew, we transitioned to optional registration with a gerund:

class User < ApplicationRecord

end

class User::Registering < User

include Gerund # disables AR's STI

validates :password,

confirmation: true,

presence: true

validates :password_confirmation,

presence: true,

if: :password_changed?

before_save :set_registered_at

after_save :send_welcome_mail

# [...]

end

See gurund module implementation

Advantages:

- Base

Useris now “barely smart data” - Can’t accidentally send emails

- Can create unregistered users

- Can register new or existing User records

- Directory/class hierarchy reveals registering is a special save behavior

- Still a PO[Rails]O (Plain Old Rails Object)

Actually using the gerunds, aka becomes

This is a good opportunity to quickly talk about various ways to instantiate inheritance-based gerunds.

At a minimum, for the above case of registering a user, we could do something like this in a controller:

@current_user = User::Registering.find([current user id from somewhere])

Some version of the above should work in any framework using an Active Record ORM pattern for domain models.

Additionally, Rails provides ActiveRecord::Base#becomes for upgrading existing objects. This is nice for when something has already instantiated @current_user since you can just upgrade it via:

@current_user = @current_user.becomes(User::Registering)

Here’s a “based on a true story” controller example:

class Users::RegistrationController < ApplicationController

def create

if !@user

@user = User::Registering.new

elsif @user.anonymous?

@user = @user.becomes(User::Registering)

end

@user.attributes = sign_up_params

if @user.save

# [...]

end

end

OK, I have lots of other loving examples, but this post is long enough. I think that makes the point.

Let’s switch gears to a comparison of a great off-the-shelf Rails architecture project: Trailblazer.

Trailblazer vs Gerunds

To be clear, I like Trailblazer. It’s done a great job of synthesizing the various architectural advice over the last decade, including thoughtful project organization and good separation of concerns. If I cracked open someone’s project and found Trailblazer, I’d be stoked.

However, like all the architectures we’ve considered, the benefits come at a cost: big buy-in, commitment, and a lot of extra jargon making noise in your domain modeling.

Using inheritance-based gerunds, I think we can do even better at a fraction of the cost.

Consider this example from the Trailblazer homepage:

class Song < ActiveRecord::Base

has_many :albums

belongs_to :composer

end

class Song::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step Model(Song, :new)

step Policy::Pundit(Application::Policy, :create?)

step Contract::Build(constant: Song::Contract::Create)

step Contract::Validate()

step Contract::Persist()

fail Notifier::DBError

step :update_song_count!

def update_song_count!(options, current_user:, **)

current_user.increment_song_counter

end

end

- We’ve ditched “convention over configuration”, which is a core source of Rails’ productivity as a framework.

- Requires more tests. What if I forget

Contract::Validate()? What if someone accidentally swapsContract::Validate()andContract::Persist()in a merge conflict? To prevent this, I’d want to test persistence and basic validation, which I’m usually comfortable not doing for most cases since it’s essentially testing Rails. - Reduced clarity. What use case is this operation satisfying? I get that creating a song has something to do with incrementing the current users song counter, but why? I also see that Song belongs_to a composer, so is the current user the composer? Not clear without further investigation.

Let’s see the Trailblazer operation as an inheritance-based gerund:

class Song::Composing < Song

include Gerund # disables AR's STI

validates :title, :composer, presence: true

after_save :update_song_count!

def update_song_count!

composer.increment_song_counter

end

end

See gurund module implementation

Advantages:

- Avoids dependency injection overkill: Because the Trailblazer operation has no class-based relationship to

Song, you must pass in dependencies - specifically, whom I assume is thecomposer, but whom the operation labelscurrent_user. Dependency injection is a fine tool, and there’s something to be said about avoiding side-effects. You could add acurrent_usermethod to keep DI, but we also have the option to instead usecomposerdirectly until such a time as we actually need DI to satisfy the use case. - PO[Rails]O (Plain ‘ol Rails Object): The gerund uses stock ActiveModel, nothing else to depend on or learn.

- Naming: IMO, the naming convention better expresses the use case, but I know naming is a very personal thing. Plus it’s had time to grow on me.

Let’s see these side-by-side:

class Song::Create < Trailblazer::Operation

step Model(Song, :new)

step Policy::Pundit(Application::Policy, :create?)

step Contract::Build(constant: Song::Contract::Create)

step Contract::Validate()

step Contract::Persist()

fail Notifier::DBError

step :update_song_count!

def update_song_count!(options, current_user:, **)

current_user.increment_song_counter

end

end

class Song::Composing < Song

include Gerund # disables AR's STI

validates :title, :composer,

presence: true

after_save :update_song_count!

def update_song_count!

composer.increment_song_counter

end

end

Woah.

To my eye, compared to a Trailblazer operation, this gerund is natural, expressive, and true to “You Ain’t Gonna Need It” (YAGNI) philosophy. Some day we might need the configurability and flexibility offered by Trailblazer, and when we do our gerunds will map well to Operations. Until then, the extra configurability is just making things much more complicated than they could be.

Fin!

This was a long post because I know I’m advocating for a lot of things that should rightfully make you go “hmmmmm.” But let’s recap.

Continue to avoid inheritance for highly dynamic runtime behavior, sharing code, and anything else you know it’s bad at.

Also continue to avoid ActiveRecord callbacks on base domain models.

Do use inheritance for procedural actions relevant to a single domain model, ex. user registration, or context-specific representations like views, emails, forms, etc. threatening to bloat your core models.

Finally, putting all this under the “gerund” umbrella lets us cover many of these needs naturally, without introducing extra layers of jargon for presenters, form models, service objects, etc.

Aaaaaaand no external dependencies, plus conceptual compatibility with many heavier-weight architectures.

🍻

Here again is what we covered:

- Why gerunds are ****ing great 🤔

- Hating on decorators 😦

- Yes, really, inheritance over composition sometimes 😦😦

- A joyful return to ActiveRecord callbacks 😦😦😦

- My own experiences growing Rails with gerunds

- Trailblazer vs gerunds

Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you in the comments!

Further reading:

Growing Rails Applications in Practice

The biggest insight from their book was using simple inheritance to implement form models. Previously I was using runtime extensions, which are structurally similar, but simple inheritance is even cleaner.

Their naming conventions didn’t do it for me, and the authors use service objects where I’d now use a gerund, but it’s a great read. You would be blessed to work on a codebase following all their advice.

Just a couple days ago I found this decorator project I hadn’t seen before. The documentation says the decorator module runs in the model's context. I didn’t know what that meant exactly, but after some investigation I see it uses runtime extension under the hood.

This means you could use ActiveDecorator without any of the drawbacks mentioned here, since it’s actually implemented with a form of inheritance.

My Ruby 2.1 project testing object extension

TL;DR, decorators will getcha and module extension is performant in Ruby >= 2.1.

Appendix

The Gerund module

Currently just disables STI, but also a placeholder if we want to ex. make view helpers more accessible in the future.

module Gerund

def self.included(base)

base.extend ClassMethods

end

module ClassMethods

delegate :model_name,

:sti_name,

:finder_needs_type_condition?,

:_to_partial_path,

to: :superclass

end

# GlobalID depends on the model to get class_name, rather than passing

# it in directly. Maybe someday we can try to get GlobalID to be easier

# to work with in this way; until then, this works.

def to_global_id(*args)

becomes(self.class.superclass).to_global_id(*args)

end

alias :to_gid :to_global_id

end