Gerunds: intelligible system behavior

An alternative to complicated object-oriented architectures, service objects, decorators, view models, etc

Welcome to my series on OOP architecture. I’ve been leading small OO and functional programming teams for almost 20 years, and I’ll be sharing ideas about growing software from prototype to the most majestic of monoliths. —

Defining the problem

If you do backend or full stack software engineering with OOP frameworks like Rails, Django, and similar, I have something I’d like you to consider.

It’s a simple, natural way to express behavior that’s either bloating models, or is spread around various architectural components like service objects, form models, presenters, and similar.

For me, these patterns are… luke warm. Spaghetti code, bloated controllers, god models - those are existential threats to the technical sustainability of your project. Luke warm is a whole lot better than being locked out in the cold, but I hope we can do even better.

After all, wasn’t it nice when your app was smaller, and your domain models were simple translations of things you saw in use cases? Sure, User had a few long methods, but you didn’t have UserPresenter, UserRegistrationService, and whatever else, all with their own interfaces and implementations to manage, none inspired by delivering customer value.

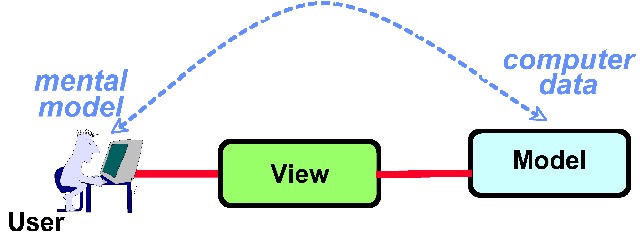

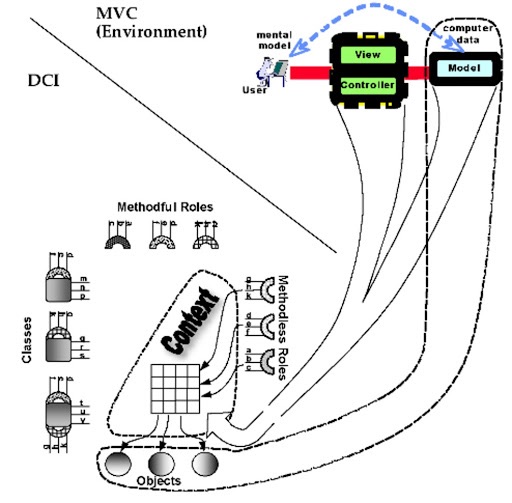

Transparent domain modeling was the original promise of Model-View-Controller (MVC). You’re supposed to spend most of your energy translating users’ mental models to code - the M - and let views and controllers expose it to the world:

The DCI Architecture: A New Vision of Object-Oriented Programming

The DCI Architecture: A New Vision of Object-Oriented Programming

Then the authors of Model-View-Controller realized OOP was missing something (and my experience agrees):

While objects capture structure well, they fail to capture system action. The DCI Architecture: A New Vision of Object-Oriented Programming, 2009

So they proposed a fix that looks like this:

The DCI Architecture: A New Vision of Object-Oriented Programming

The DCI Architecture: A New Vision of Object-Oriented Programming

Oomph. I think DCI is really smart, but especially compared to the simplicity of MVC, if you just want to put a bit of registration logic somewhere other than User it’s not worth pulling in all that extra jargon. I don’t need a Context to manage a Role to extend the User so it can participate in a registration Interaction.

My goal is to grow a project as long as possible with a small team and little-to-no ideological lock-in. People - including myself some time later - should be able to come in to a part of the code and get to work without having to remember the architectural jargon that was trending at the time. There’s got to be a better way!

My goal is to grow a project as long as possible with a small team and little-to-no ideological lock-in.

Let’s skim over how some other common architectures fare in terms of complexity and jargon.

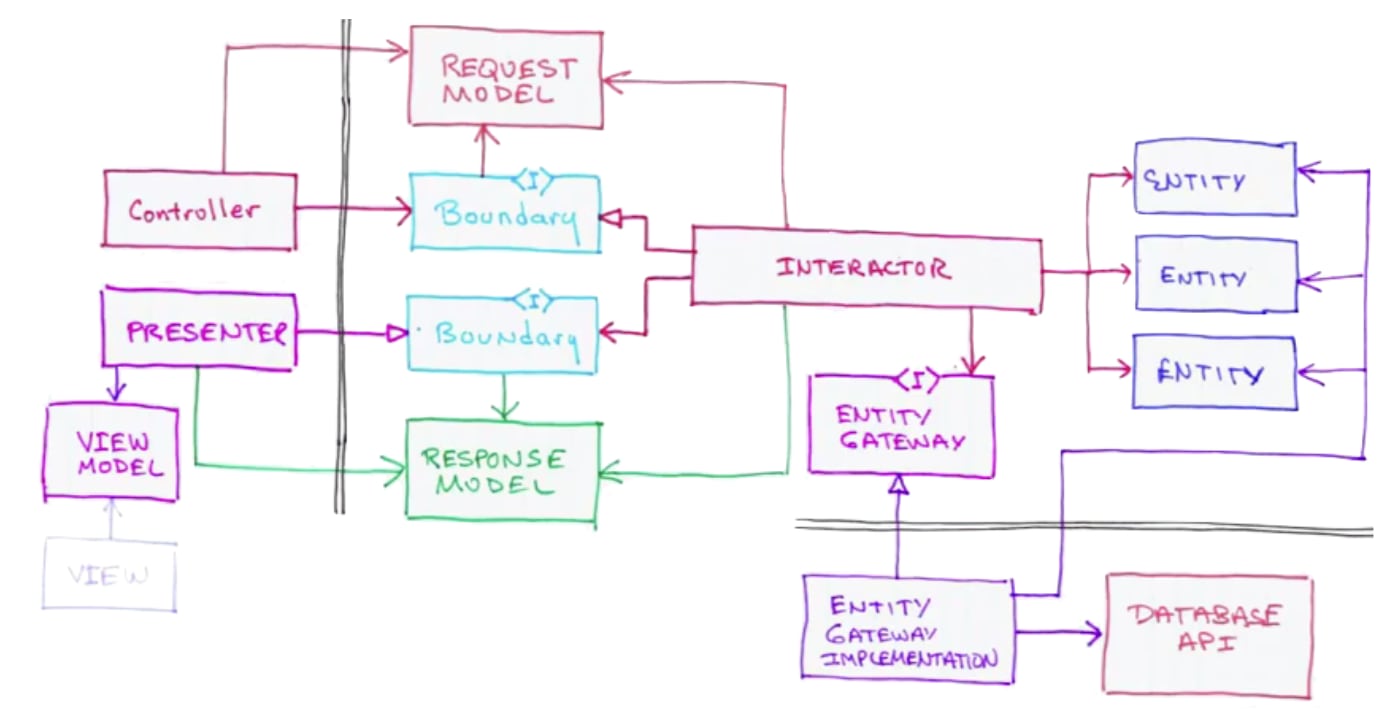

Robert Martin’s “Clean Architecture”?

- Entities “business objects”

- Interactors “business logic”

- Boundaries feature API

You pass data blobs (ex. JSON) as messages between components. In addition to entity+interactor+boundary modeling, don’t forget we still have presenters, view models, and request/response models to fully grok a particular use case. There’s got to be a better way!

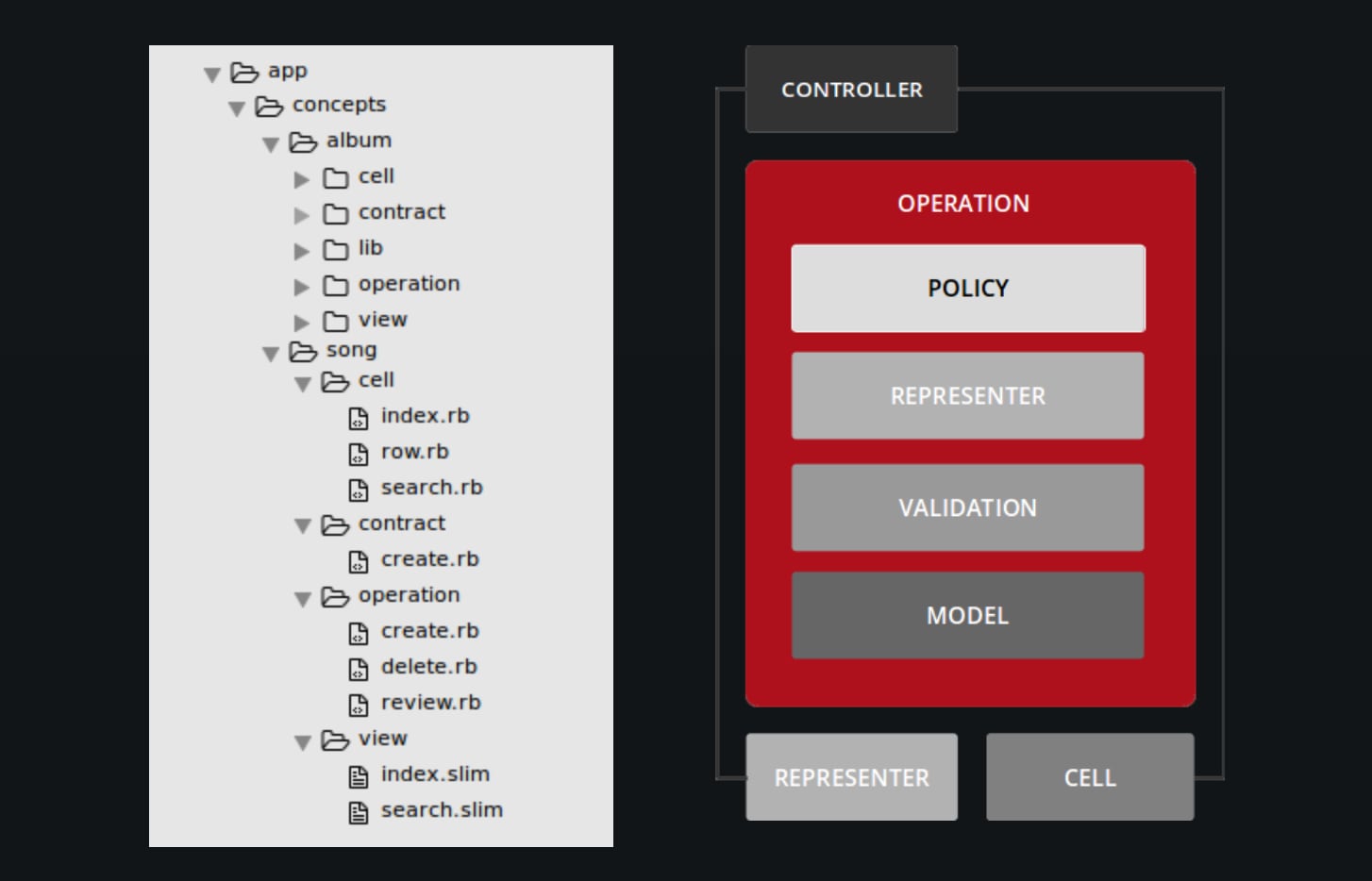

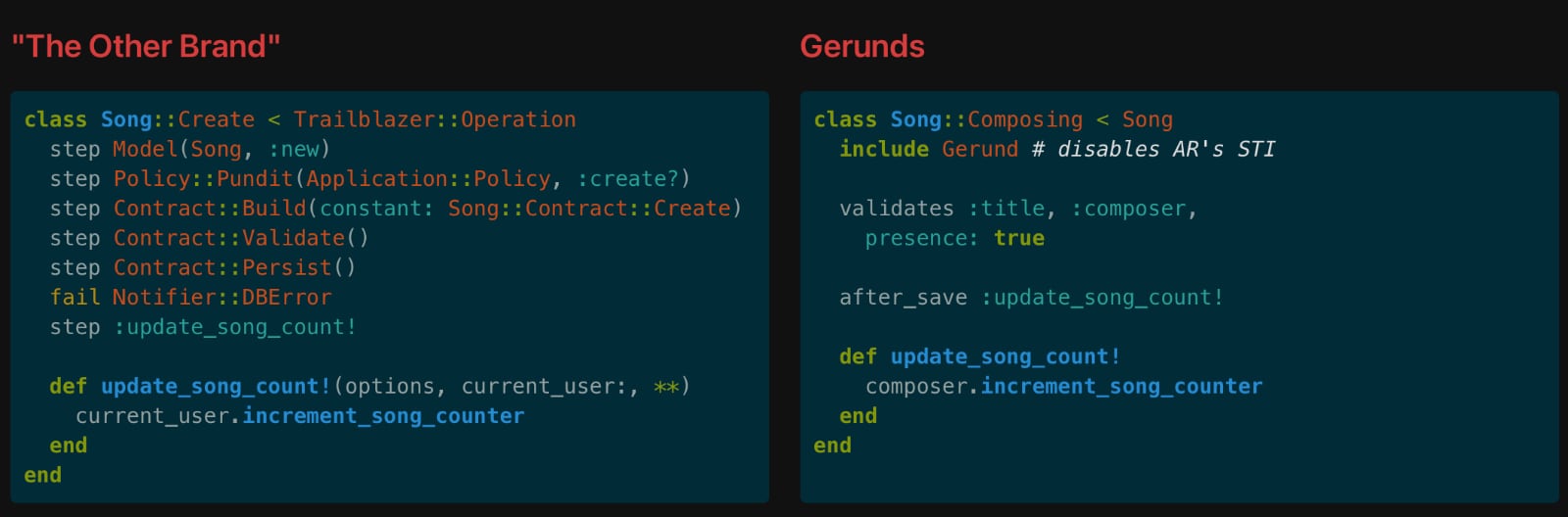

Trailblazer?

From their documentation:

- Contract Form objects to validate incoming data.

- Policy to authorize code execution per user.

- Operation A service object implementation with functional flow control.

- View model Components for your view code.

- Representer for serializing and parsing API documents.

- Deserializer Transformers to parse incoming data into structures you can work with.

I’ll say again, anything is better than a god model or an epidemic of controller bloat, but all I want is a place to put user stories into code. This still seems like overkill. There’s got to be a better way!

Gerunds? Gerunds!

A gerund is all the code for a particular business concern, built by extending a core “barely smart data” domain model.

Consider Post::Publishing or User::Registering, which in addition to the core Post or User behavior could include additional validations, attributes, callbacks, side-effects, special presenter display logic, even potentially URL generation and custom routing. That’s not great w.r.t. the single responsibility principle, but the value of colocating all the code to satisfy a use case can’t be overstated. If it becomes too much for one class, you can of course use any other OOP technique to further separate responsibilities as needed.

In my opinion and experience, formalized architectures like DCI introduce too much custom jargon and emphasize the single responsibility principle, at the expense of code colocality. I want my business logic to tell a story while prioritizing DRY, the open-closed principle, and colocality. Single responsibility is great for lower level building blocks and domain modeling, but usually obfuscates business logic.

Why gerunds are ****ing great

A large part of the value lies in a naming convention, but it’s new and weird and engineers argue about names constantly so it deserves many words.

How do we express actions in natural language? With gerunds, aka -ing words:

Gerund: a verb that acts as a noun, ending in -ing, becoming the subject or object of a sentence

subject enjoys

verb drinking

object Your order

subject is

verb processing

object When the user

subject is

verb registering

object

So when we talk about a subject performing actions, the verb becomes the object.

Hey, wait, we do “object-oriented” programming right? Why haven’t I used a gerund in code then?

Well, I think we can use this fact of grammar to consider changing the way we name system actions, thereby improving the expressiveness of our domain models.

Gotta put the code somewhere

In my experience, this is how a lot of behavior starts out: instance methods on core domain models (yuck):

1

2

3

Order#process

User#register

Product#decrement_qty

Eventually, someone makes service objects (yay!):

1

2

3

Order::Processor#process

User::Registrar#register

Product::Updater#decrement_qty

Why does every object have to be a noun though? Since -ing words are literally the object of the sentences we use to describe actions, what about:

1

2

3

Order::Processing#save

User::Registering#save

Product::Updating#save

I used #save here because that’s what triggers ActiveRecord callbacks

Make Ruby natural, not simple, in a way that mirrors life.

— Yukihiro Matsumoto

Well, I have been finding the gerund style to be a much more natural way to model action than the usual service object nomenclature:

- It reads well (the class name plus method signature makes a valid sentence).

- Calls out the transient nature of the operation

- Naturally inspires a consistent interface (always calling

#save).

Using inheritance here is admittedly a bit of a hack. Inheritance usually describes an “is-a” relationship, and we’re writing code that describes “is-currently.” In some more perfect implementation it would be its own first-class thing, perhaps, but this works fine.

Actually using the gerunds, aka becomes

At a minimum, for the above case of registering a user, we could do something like this in a controller:

1

@current_user = User::Registering.find([current user id from somewhere])

Some version of the above should work in any framework using an Active Record ORM pattern for domain models.

Additionally, Rails provides ActiveRecord::Base#becomes for upgrading existing objects. This is nice for when something has already instantiated @current_user since you can just upgrade it via:

1

@current_user = @current_user.becomes(User::Registering)

Here’s a “based on a true story” controller example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

class Users::RegistrationController < ApplicationController

def create

if !@user

@user = User::Registering.new

elsif @user.anonymous?

@user = @user.becomes(User::Registering)

end

@user.attributes = sign_up_params

if @user.save

# [...]

end

end

In Ruby we can also use multiple inheritance via modules, then extend objects at runtime. I’ll do a separate post on that.

Addressing concerns

You’re probably thinking one or more of the following, for which I’ll write separate blog posts. In short:

Q: “OK but what’s wrong with service objects?”

A: Feature envy, awkward naming, more interfaces to manage. That said, sometimes service objects do still make sense, especially if the behavior spans multiple domain models or is not user initiated, ex. a nightly backup job.

Q: “How is this different than delegators?”

A: “It’s a trap!” Delegators are deceptively awful, IMO. Deserves its own article.

Q: “Shouldn’t we prefer composition over inheritance?”

A: Sure, sure. I’m using inheritance - including multiple inheritance, which we haven’t discussed here - as an implementation mechanism. Gerunds should be edge nodes in your (hopefully shallow) inheritance tree. It’ll be fine.

Q: “Does AI and the growth of vibes coding make architecture irrelevant?”

A: Maybe! Who knows for sure. I’ll say currently, tasking AI with greenfield development is much more reliable than modifying or refactoring large technical-debt-laden systems. With gerunds, since each file is small and task oriented, it should in theory help keep AI systems productive for longer.

I’ll add follow-up links on these topics as I go more in-depth.

Call to action

You can try gerunds in some form right now to see how it feels via inheritance and the naming convention.

To use them in the full request/response cycle in a Rails project, you will need a small module to tweak ActiveRecord’s assumptions about inheritance.

If it turns out to not be what you need, you’ll already have well factored code ready to be converted to whatever you prefer - Trailblazer operations, service objects, etc.

I’ll be writing more in-depth articles on architecture and gerunds in the near future, so let me know if there’s a particular area to expand into.

Happy coding!